Managing OSS Transformation Risk

A reader of Mastering Your OSS recently reached out to indicate that he found Chapter 7 useful for understanding OSS-related risks and mitigations. He pointed

What happens when a Software Engineer, Enterprise Architect and Network Ops Engineer walk into a bar?…..

.

You know that head-slap moment when you realise software is more hindrance than help?

I had one such experience back in circa 2005, when I watched a genuinely brilliant network ops engineer spend an entire afternoon navigating tools trying to do something he already understood…

…But couldn’t.

It was then reinforced when really capable engineers at other telcos experienced the same problem.

But the failure wasn’t human (well, it was, but wasn’t. We’ll get back to that).

The failure was a system that had not been designed with real use or real scale in mind.

There was nothing the expert users could’ve done to make the product work effectively, or even work properly at all for that matter.

.

But if we go back a couple of steps, the failure was VERY human.

I knew the system’s designer. He had no real world experience. He’d never even sat in a real NOC (network operations centre), let alone done the role of the network ops team.

That in itself was not the problem. There were two related problems:

We invited the designer to site. He refused. We invited him to join a call with the users. He refused.

He wasn’t interested. In his words, the product was “perfect” and the users were just incompetent and needed to be trained better.

Sadly, his attitudinal logic was as flawed as the logic of the code he’d written.

.

The seed of this article crystallised when the following quote reminded me of c2005:

“Power does not come from complexity, it comes from leverage. Tools that remove friction expand what a person can reasonably attempt. When capability increases without added burden, judgement finally has room to matter.”

Guney Topcu

I didn’t fully understand it at first. I had to re-read it a few times.

We build systems to control outcomes. However the best outcomes happen when we give people leverage by removing complexity / friction. We free up their time to focus on the more important challenges by reducing the effort they allocate to the mundane.

.

I’ve spent decades in the telco software space, watching smart users struggle with powerful tools, Topcu’s quote started to feel uncomfortably accurate. Too uncomfortable!!

.

Early in my career, I was all about the tech. I was the stereotypical Engineer. I assumed complexity was the price of seriousness. The more important the system, the more screens it had to have. The more rules it had to have baked in. The more edge cases it had to cover. The more process steps it required.

That logic felt reinforced in everything we designed, built and did – from enterprise platforms, transformation programmes, to “best practice” frameworks that promised delivery and control at scale.

But over time, something didn’t add up.

The scale equation was back-to-front. Scale (in hours/days) to solve the problem rather than solving the problems at scale (in seconds/minutes).

When you’re spending time on-site with the real users, poor design is incredibly frustrating to watch.

Enterprise systems tend to exist for scale. The sheer volume of a company’s transactions (eg processing orders) justifies the cost of building and maintaining the system.

When the most capable experts are spending their days navigating enterprise systems and plugging in unnecessary data instead of solving problems, there’s a problem with the design.

Sadly, that’s commonplace in the telco world.

There was one vendor that I worked with about 15 years into my career. I took about 6 months of using the software before feeling competent with it. Sure, every product requires a familiarisation / apprenticeship period, but 6 months was too long.

I could only imagine what the experience would’ve been like for someone without the 15 years of context and/or users who only needed to use it intermittently!

Now, with new advances in AI/ML and automation, Topcu’s quote becomes even more important!

.

Regardless of whether OpenAI’s ChatGPT is seen as revolutionary or not, there can be no argument that its User Interface / Experience (UI/UX) has changed the game. It took the highly complex world of AI/ML and made it accessible to the masses, in the same way that Google had revolutionised the experience of searching the web beforehand.

If nothing else, ChatGPT gives us an opportunity to totally reframe the way we think about Enterprise software design and digital transformations.

Most digital transformations start from the concept of encoding existing processes into software. I’ve seen this play out repeatedly in telco. Approval chains become workflow engines that coordinate rather than reduce the manual work. Decision trees become rules engines, but trees become unnecessarily more complex because we have more processing power at our disposal.

The result looks impressive on a slide. But do they actually create more work whilst quietly shifts power away from humans?

Contrast that with how Stripe approached payments. They didn’t start by modelling every possible financial process. They focused on removing friction for developers. One API call replaced weeks of negotiation, contracts, and manual setup. Capability increased without adding burden.

That difference matters. One approach scales control. The other scales people (unnecessary effort).

.

However, generative AI has the potential to introduce a problem. GenAI tools are great at creating “volume” quickly. It’s really easy to use them to create greater complexity (more screens, more rules, more edge cases, more process steps, etc) rather than using them to create less (subtracting the suck).

.

Great products are ruthless about what machines should handle.

When Google built search, they didn’t ask humans to curate the web. They automated crawling, ranking, and filtering at an unimaginable scale, then presented a single, meaningful result. Humans didn’t get more work. They got more reach in a curated list.

ChatGPT took it a step further to reduce even more friction, which is arguably why it gained massive AI/ML mindshare so explosively.

.

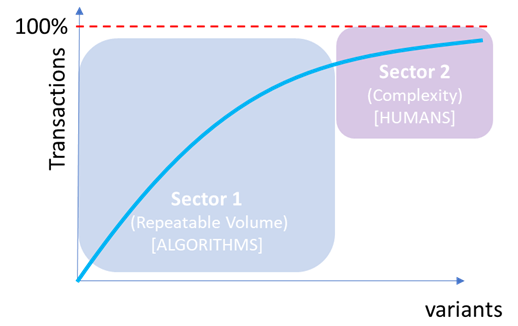

Most enterprise software, especially those used within telco, was originally designed with a user interface for for humans to handle volume (blue – sector 1 in the diagram below) in an efficient manner.

But here’s where things get interesting. Most modern enterprise software should allow algorithms to handle the volume (blue box below), leaving humans to only handle what the machines can’t (maroon box below).

The way we design software to handle volume (sector 1) is very different to the way we design software to handle the rare / unique / complex (sector 2).

I call this new mindset “the bubble-up factor” (ie humans should only handle what bubbles up after the algos have removed most of the friction and repetitive volume).

.

We also see it in the software feature vs value development long-tail diagram below.

Instead of using genAI to rapidly generate more features to the right of the tail (the long blue arrow that doesn’t really add much value), we can consider how the red box can be reinvented with the bubble-up factor in mind.

I’m sure you’ve seen the same pattern inside your organisations.

Teams drowning in volume, repetition, noise and friction, increasing their burden, rather than having the tools that give them leverage.

.

The remainder, the parts that bubble up after the algos have done their job, is where humans earn their keep.

Complexity. Ambiguity. Trade-offs. Risk. Context. Human decision gates. Black Swans. These are not problems to handle computationally. They are judgment problems that still require human involvement (at this stage anyway).

You see this clearly in how Steve Jobs talked about tools. The iPod wasn’t a hit because it exposed complexity. It was a massive success because it hid it. It allowed humans to manage their music and playlist, not focus on the mechanics of the MP3 player.

In systems that respect judgment, experts are pulled in only when things are unclear or ambiguous.

In systems obsessed with control, experts are buried under procedure. They follow the process not because it’s right, but because it’s safer, more reliable and more repeatable than giving your team greater leverage, insight and room for thinking.

.

The most admired modern tools do something subtle. They shrink the work before you notice it.

Notion doesn’t ask you to choose a database schema before you write a note.

Figma doesn’t make designers manage files and versions.

The complexity exists, but it’s compressed out of the way.

Twinkler does the same for radio planning. Most radio planning tools give the user the option of setting hundreds of variables. Twinkler allows control over those variables too, but hides most of them away, using default values, leaving only the most impactful variables on the main user interfaces. This allows designs to be done by novices in minutes.

In operational systems, the same principle applies. Automated remediation that acts within guardrails. Defaults that remove hundreds of micro-decisions. Interfaces that surface meaning instead of data.

Not removing the complexity, just leaving it hidden unless needed in rare cases.

This approach reduces cognitive load of the user.

Each one expands what a single person can attempt and how quickly they can become productive.

.

In leveraged systems, work feels calmer. One person can do what used to require a team.

Decisions happen faster, even with less information, because the noise is already gone.

Volume / throughput is greater because many of the delays are effectively removed from the user’s workflow.

The transformation metric isn’t tool count or process coverage. It’s effort removed.

.

But here’s the really interesting thing:

As Guney Topcu observed, power does not come from the intellectual brilliance of additional functionality (ie complexity). It comes from leverage (which generally equates to complexity / noise / volume / friction reduction).

PS. So anyway, the Software Engineer, Enterprise Architect and Network Ops Engineer walk into the bar and the bartender asks, “what’ll it be?”:

A reader of Mastering Your OSS recently reached out to indicate that he found Chapter 7 useful for understanding OSS-related risks and mitigations. He pointed

Have you ever wondered why there’s such a big deal made of the start of a marriage (there’s a whole industry built around engagements and

Whether we like it or not, most of us judge books by their covers. Sometimes that’s visual. Sometimes it’s the title. But here’s a thing

The last four articles have explored the way some telcos are using AI technologies counter-productively today – AI entanglement, transformation planning, dependency visibility and the