12 reasons why our OSS get better by wearing hi-viz vests

Ever noticed how many OSS decisions are made by people who have never set foot on site? What if your single most powerful OSS upgrade

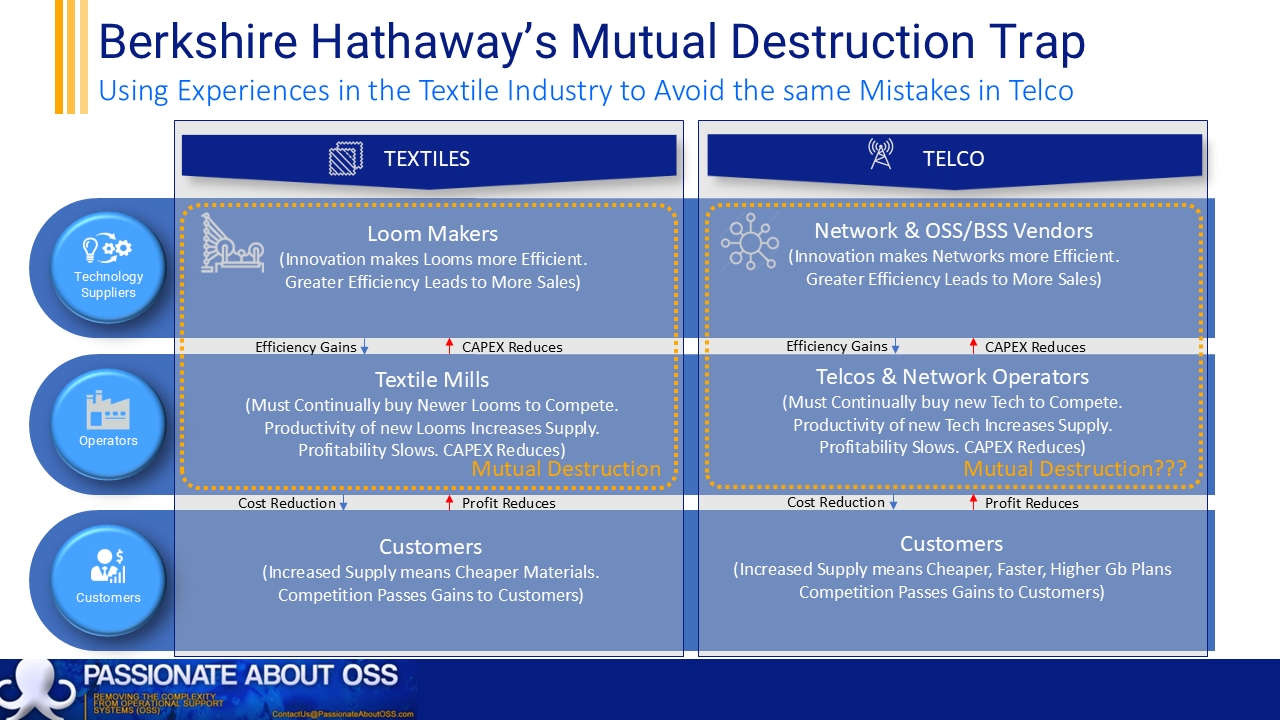

The story of Berkshire Hathaway is a famous one. It started in textiles but Warren Buffett chose to drastically change strategy because the textiles industry was dying. You’d have to say his decision has proven to be correct. If it stayed in textiles, Buffett would almost certainly not be as famous as he is today.

There are strong similarities between the textiles industry back then and the telco industry today. But this story isn’t one about an industry in the doldrums. It’s a story of possibility.

Buffett’s great friend and business partner, Charlie Munger, talks about this strategic shift in his book, Poor Charlie’s Almanack.

It teaches that when technology innovations boost productivity in commodity markets, benefits often flow to customers or upstream suppliers / innovators, not to the firms adopting the tech:

.

Charlie’s textile parable is brutally relevant for the telco industry. He argued that the great lesson in microeconomics is knowing when technology helps you versus when it kills you. In textiles, faster looms cut costs, competition pushed savings through to customers, and mill owners earned increasingly poor returns.

Seeing this writing on the wall, Berkshire decided to shut the last of its mills in 1985 and redirected capital into more profitable businesses (such as insurance and regulated utilities). The moral was not anti-technology, it was pro-capital reallocation when the industry structure guarantees pass-through of gains to others.

1985 marked the end of its original textile business, transitioning fully away from manufacturing textiles to become the diversified conglomerate known today. Buffett, who gained control of the company in the mid-1960s, has described the textile business investment as his biggest mistake due to its long-term decline.

Telecoms shows the same mechanics. Ofcom reported that prices per mobile basket in the UK fell materially in real terms from 2019 to 2024 even as data consumption nearly trebled. Classic evidence that productivity has been competed away to end users. Across Europe, policymakers note broad 5G coverage and fibre build-out, yet sector returns trail rising WACC. BCG quantify the gap: median telco ROIC around 6.7% versus WACC around 7.1% in 2024, which destroys value even when networks get more efficient.

That is Munger’s dynamic with a RAN rather than a loom!

Just like the mills that did all the hard work making the materials, the telco connectivity ecosystem is a major enabler of competitiveness, sustainability, security and resilience.

.

In a competitive industry themselves, loom manufacturers kept innovating, perfecting the efficiency of their looms. Doubling down on feature velocity and incremental automation whilst raising prices to maintain their own shareholder returns. But this only accelerated a mutual destruction loop. The innovation exacerbated the benefit split further, giving the advantage to the manufacturers and customers, but leaving the mill operators in a race to the bottom in terms of price and profitability.

With the mill operators becoming unprofitable, it left no CAPEX to spend on “the 6th G” of looms.

Clearly the telco and textile industries are vastly different in many ways. But if I look through the textiles lens, it does feel that OSS/BSS and network vendors might already be facing the same trap. After the major investments waves in 5G and cloudification, I keep hearing the same negative sentiments from suppliers. Telcos just aren’t buying like they used to.

.

It’s not a case of what WOULD they do. It’s a case of what they DID do.

Berkshire’s answer was not “better looms”, it was reassigning capital to industries where structure supports durable returns. As Buffett himself admitted, his continued involvement in the textile industry was his biggest mistake.

I’m not suggesting quite the same peril for telco, but I am suggesting we can’t just continue to “optimise the loom.” We must do what Buffett did and think differently. Vastly differently!

Telcos simply aren’t positioned to lead that kind of pivot on their own. Their governance, regulation, shareholder expectations and leverage make large disruption bets nearly impossible to consider.

That leaves their suppliers – the modern loom makers, namely OSS, BSS and network vendors – to lead the way. It requires a total re-think about reallocation of capabilities into higher-moat profit pools, while pulling operators along as channels, co-investors or JV partners.

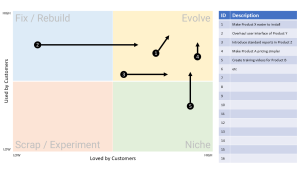

.

This is where I start to get a little bit speculative. I know radical disruption of the telco business model is required, but there are much cleverer people than me to suggest how. What follows is just one possibility.

1) Turn OSS/BSS into BOS (Business Operations Systems) that sell outcomes beyond telecoms

Our OSS/BSS of today already contains the same capabilities that every operating business needs:

It’s just that today’s OSS/BSS tools are designed for internal use by the telcos (and with an inward-facing intent).

Re-packaging these same capabilities for external use, as coherent Business Operations Solutions (BOS) for the telco’s existing business customers, brings a customer-facing intent (and delivers value to customers). These business customers already use the types of tools mentioned above, but need to integrate for themselves at great expense and effort. There’s room for drastic improvement in this space.

And there are live beachheads. We already see billing, CRM, GIS and ITSM platforms straddle both communications and energy industries (and many others too). This proves the cross-vertical portability of our solutions. This part is not speculative. We only need to show how a telecom-hardened operating layer can lift productivity in other industries, to standardise and scale.

Even better, can we actually add even more value to customers by helping them with their business issues such as lead-generation, supply chains, customer acquisition, partnerships, using “customer connecting” BOS like the model shown below? Could carriers look outward to facilitate opt-in BOS partnerships that deliver more value to their large subscriber bases, empower stronger supply chains, and protect those chains with network-grade security?

.

2) Lead telcos into energy, where returns can be regulated or contractually anchored

As mentioned above, we’re already seeing the rise of multi-utility telcos.

With the advent of renewables, the energy sector moving from central power generation (ie power plants) and is fragmenting into millions of edge assets – EV chargers, batteries, rooftop solar, flexible loads – all of which need inventory, orchestration, assurance, settlement and field ops. The most flexible of network inventory tools are able to handle any type of asset and network topology, whether comms, power, water, roads or more.

An OSS/BSS vendor in partnership with their telco can ship “BOS for energy” that includes DER enrolment, tariff engines, dispatch and settlement, outage workflows, plus pay-as-you-save contracts that align fees to verified kWh savings for enterprise estates. This does not abandon telco, it compounds it, since network sites themselves are energy-intensive and can be enhanced within the same platform economics.

.

3) Operate the BOS for data centres and edge compute estates

As Sam Altman suggests, compute, power and connectivity form the holy trinity for AI and intelligence. Vendors can extend inventory, assurance and policy into a DC:BOS that ties capacity, energy and workload placement to measurable SLOs across central and regional (and maybe even edge?) facilities.

Global operators and carriers are monetising or expanding DC footprints, signalling predictable demand for a standardised operations system. Massive investments are also being made into grid re-profiling and energy capacity expansion. Again, perfect for a telco-delivered BOS.

.

Regardless of what disruption lever (or levers) we invent, the contractual model could matter as much as the product.

To escape the mutual destruction loop, vendors almost certainly need to move from licences and revenues coming from the carriers to aligned economics.

Partnership!

In many cases partnership is a dirty word in the current world, with procurement contracts that are flawed from the outset.

.

There are risks. We all know there are risks!

.

The alternative is the textile loop.

If vendors keep perfecting the same looms – incremental OSS/BSS features, one more automation layer, the next G – then productivity improvements will keep flowing through to vendors and customers as cheaper per-GB. But vendors will find themselves with fewer telco clients able to pay.

As long as operators remain under WACC ,vendors face squeezed margins as capex (and OSS/BSS projects) stalls.

Both vendor and operator simply become more fragile into the next cycle.

Buffett and Munger’s answer was to move the capital and the capability into entirely new industries, ones where economics allowed value to stick.

For telecoms, that means vendors leading a pivot from inward-facing OSS/BSS to customer-facing BOS – packaging the same hard-won primitives to power energy, data centres, rail, ports and all other forms of digital enterprise – and pricing against outcomes those industries will fund.

What are your thoughts. Is it really as dire as this? Do we desperately need to turn mutual destruction into mutual creation?

Ever noticed how many OSS decisions are made by people who have never set foot on site? What if your single most powerful OSS upgrade

Are you frustrated by the complexity of your OSS/BSS factory? With hundreds or even thousands of systems, all trying to juggle thousands of activities without

Are you worried that your OSS/BSS stack, or parts of it, might be in desperate need of an overhaul? Many OSS experts love being archaeologists,

Most OSS/BSS roadmaps today overflow with novelty and buzz. You might even hear the words Agentic AI come up (not that I have anything against